Photo by: http://www.dailysabah.com

Author: Marián Šeliga

Slovakia and Poland: competition for cargo routes

The war in Ukraine has plunged BRI projects in the CEE region into great uncertainty. Against this background the prospects of the BRI projects as well as the planned investments in the region look somehow bleak and unclear.

In the second article in a series of articles devoted to the Belt and Road Initiative in the CEE region we will look at the current situation with BRI projects in Poland and Slovakia and especially at the transport corridors going through these countries. The transport routes within the so-called New Eurasian Land Bridge play a significant role in the BRI cargo transportation from China to Europe. Today, Poland enjoys the status of BRI logistic hub for BRI in the CEE region, which brings additional revenue to the Polish state budget. Being somehow sidelined in the BRI transportation system by external factors (the instability in Ukraine before February 24, 2022) and by internal factors (lower tariffs on cargo transport in Poland), Slovakia has nevertheless shown a tireless ambition to participate in the logistic operations of BRI, especially when taking into account its advantageous position in the CEE region (the intermodular connection with Budapest and Vienna).

China-Poland relations: rollercoaster dynamics from friendly to complex and back to friendly

The development of Polish-Chinese relations over the past 10 years has been like a rollercoaster ride, from deepening relations to losing optimism, and then back to cultivating a once-damaged relationship. In the first period of deepening mutual cooperation a fiasco occurred when the Chinese state-owned company building part of the Polish highway was unable to finish the project, which led to a deterioration in relations between Poland and China. After a long period of stagnation in relations, cooperation between the two countries is gradually improving now. This has been demonstrated especially by the the growth in revenue from freight transport within BRI land corridor. Although we have witnessed an apparent “cooling” of relations between the EU and China recently, during his last visit to China in February 2022 Polish President Andrzej Duda reaffirmed Poland’s desire to become China’s gateway to Europe.

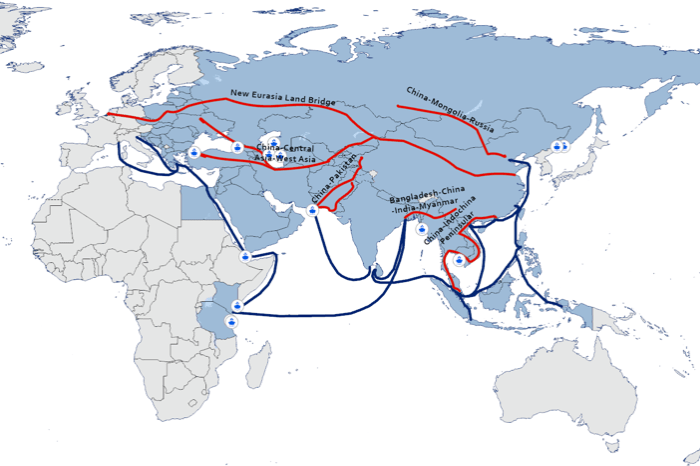

The six economic corridors of the BRI include (source: OECD. Chinas-Belt-and-Road-Initiative-in-the-global-trade-investment-and-finance-landscape):

- New Eurasia Land Bridge: involving rail to Europe via Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, and Poland.

- China, Mongolia, Russia Economic Corridor: including rail links and the steppe road

- China, Central Asia, West Asia Economic Corridor: connections with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyztan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Turkey.

- China Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor: including countries like Viet Nam, Thailand, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Malaysia.

- China, Pakistan Economic Corridor

- China, Bangladesh, India, Myanmar Economic Corridor

When analysing the Chinese railway cargo flows moving from China (as up to February 24, 2022) we will find out that the absolute majority of cargo transported by railway goes through Poland (Russia-Belarus corridor) which leads to increasing revenues of Polish cargo terminals, transport and railways companies. Against this background, Slovakia and Hungary are trying their best to compete with Poland in order to get their own cargo railway route from China. Slovakia has been unsuccessful so far in its ambition to redirect at least a part of these cargo flows coming to Poland. At the same time, amid the current uncertainty with Ukraine, the whole idea of a new BRI cargo route has lost momentum for an unspecified period of time. One of the current priorities of the respective governments in the CEE region including Slovakia is the acute transportation of Ukrainian grain by cargo trains in order to overcome possible food crisis, as the seaborne ports in Ukraine (including ports in Odessa, Pivdenny, Mykolajiv, Kherson) are closed due to the military operation in Ukraine.

What has happened to BRI route in CEE region after 24 february

It goes without saying that the war in Ukraine suspended most of the planned BRI projects in the region of Central and Eastern Europe. Chinese companies are reviewing their mergers and acquisitions in the region, as they clearly understand all the potential risks associated with the war in Ukraine. Ukraine is bordered by three of the 4 Visegrad countries (Slovakia, Poland and Hungary), therefore the security situation there coupled with the sanctions against Russia bring not only explicit unprecedented challenges to these countries which, we have witnessed practically immediately (including increasing immigration flows and disrupting supply chains), but also indirect consequences which will only gain momentum in the following months. This may include soaring inflation, rise in commodity prices and production inputs, higher unemployment as well as social and political tensions. With a direct impact on the investment environment in the region of Central and Eastern Europe these factors prevent Chinese investors from engaging in larger investment activities in the coming months.

We expect that this is going to be a significant problem for the coming months and even years. It may be noted (that if Putin informed Xi about his plans on Ukraine during Beijing Olympic games), Xi definitely might have told Putin that in case of protracted war in Ukraine the BRI land route and BRI projects in Europe would face high risk. And this is actually happening now. On the other hand, the BRI project on the whole is complementary to the long term interests of Russia which is building its own Eurasian Economic Union project. This of course may be changed (especially if Russia would need more help from China), but on the whole Russia is not very interested in the Chinese project.

War in Ukraine poses threat to the “Iron Silk road”

As we mentioned previously, Poland enjoys a strategically important geographic position along the New Eurasian Land Bridge. This railway-cargo corridor sometimes reffered to as “Iron Silk Road” encompasses railroads to Europe via Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, and Poland and it is a vital part of the whole Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) land route. It is highly possible that the conflict in Ukraine will push China to abandon the New Eurasian Land Bridge. In order to retain its cargo flows to Europe, China will rely further either on maritime routes or will use more of BRI’s Central Asia-West Asia (CAWA) Corridor and the Turkish Middle Corridor for land rail connectivity to Europe. This will inevitably lead to an increase in transportation fees, as these routes are more complex in terms of logistics. On the other hand, the current situation will create new challenges and business opportunities for countries along these routes, especially for Turkey, Iran or Kazakhstan. Turkey is the ultimate beneficiary in many aspects, as it can use the whole situation around Ukraine to advance its national interests: to provide capacity for new cargo flows from China to Europe, to become one of the most popular holiday destinations for Russians, and also to use the case of Finland and Sweden joining NATO in order to use his position in NATO and demand some compensation.

A war in Ukraine could deal a devastating blow to one of BRI’s most successful projects: the New Eurasian Land Bridge. Moreover, countries such as Slovakia and Hungary have again found themselves on the sidelines of the BRI, and their plans to largely cooperate on cargo flows from China now seem bleak. At the same time, other countries like Turkey or Iran may play a key role in the long underestimated Central Asia-West Asia (CAWA) corridor, which could become the dominant land route for BRI.

Subscribe to Globinsider now and get the newest up-to-date information on the BRI as well as for other international topics for free.